The Hidden Truth in the C-Suite

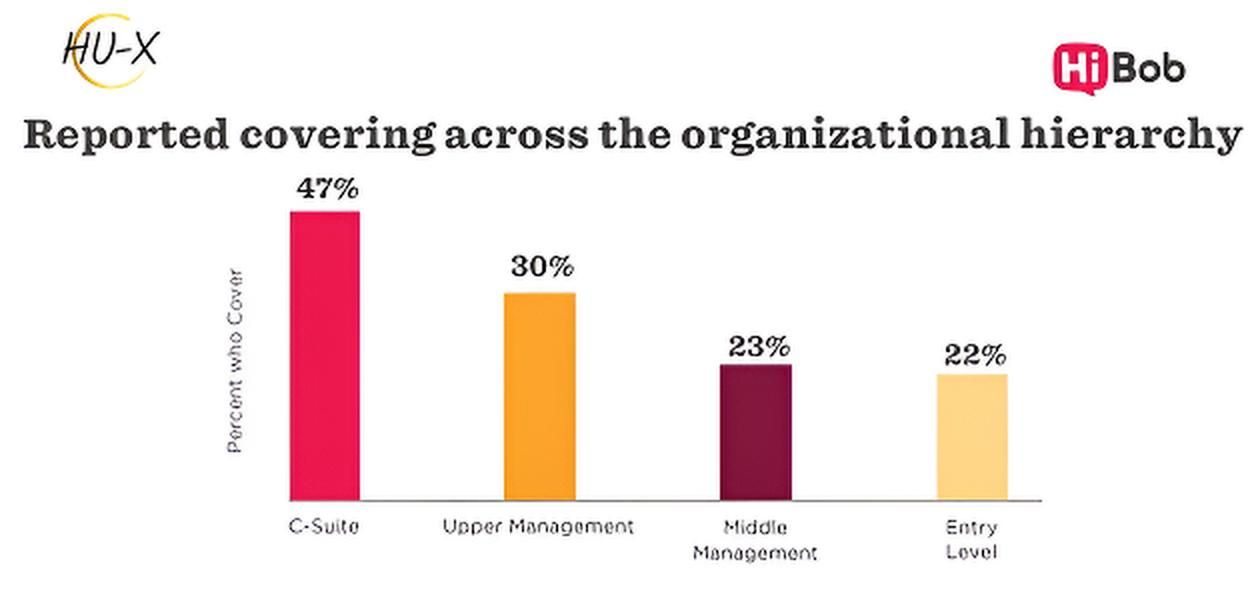

Senior leaders hide more of who they are than any other group in the workplace. In our study of 2,000 U.S. employees, the C-suite reports covering—intentionally downplaying or hiding aspects of themselves to fit in—at least sometimes across an average of 47% of the dimensions we measured. This is significantly higher than upper management at 30%, middle management at 23%, and entry-level employees at 22%.

Covering is normal. But when leaders consistently hide meaningful parts of themselves, the cost compounds: energy drains, stress rises, and performance suffers, especially in the C-suite. This pattern echoes Deloitte’s “Uncovering Talent” research: the higher people rise, the more they conceal. Kelly Bean, Head of Executive Development Programs at Hu-X, notes, “I rarely meet a C-suite leader who isn’t hiding some important part of themselves. The higher they rise, the more they fear the cost of being fully seen.”

What Leaders Are Hiding—and Why

In our data, C-suite leaders are more likely than others to downplay personal details such as sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, changes in marital status, and education level.

The personal attributes most often covered are social class, concealed because they disrupt unspoken norms of executive legitimacy, and age, a trait that has become a proxy for future relevance. Older executives worry they’ll be seen as less adaptable, less AI-literate, or closer to exit than growth. Younger-than-expected leaders fear being viewed as insufficiently seasoned, promoted too quickly, or lacking gravitas.

C‑suite leaders also report higher levels of covering around religious affiliation, socio‑political views, disabilities, physical and mental health, being introverted, caregiving responsibilities and self-care routines, such as taking an hour from the day for a doctor’s appointment. Nearly half say they hide their true mood at work, adding an additional layer of emotional labor which has been long associated with exhaustion and diminished well-being.

These anonymous responses from our study illustrate the emotional toll of covering, even for the most senior executives.

- “I often cover how tired I am or how much workload I have.”

- “I decided to cover my real age. I avoided mentioning my long years of experience in the field, and focused only on my recent accomplishments. I became less confident in expressing my opinions based on my long experience.”

- “I have epilepsy and have had seizures. When hired, I kept this to myself.”

- “I had to change my hairstyle and how I talked. It made me feel a type of way… why do I have to go through this. Just let me be me.”

How often C‑suite leaders cover shows this coping behavior has normalized. Roughly 80% of executives in our study say they cover with almost everyone around them, including HR, their direct manager, their own teams and colleagues across the organization. These rates are noticeably higher than those at lower company levels.

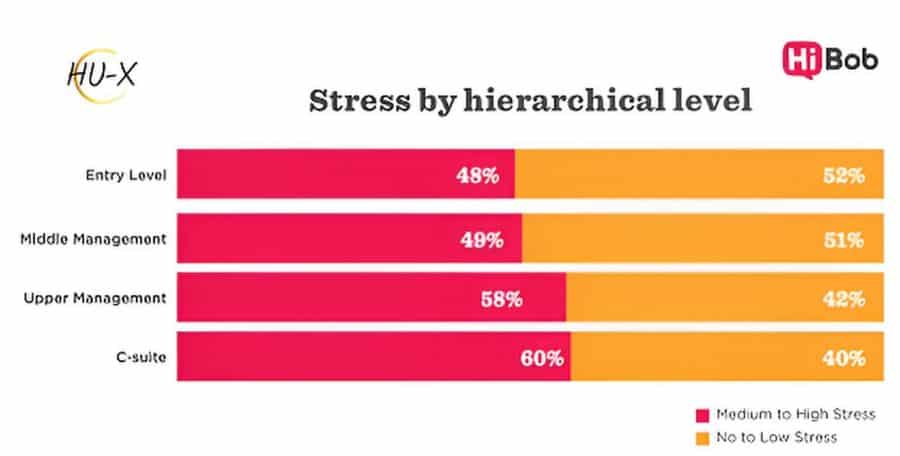

C-suites mostly cover to maintain a “professional image,” but this comes with a cost. 60% of C-suite survey takers report experiencing medium to high stress due to covering, along with the usual day‑to‑day demands of their roles. More than half of C‑suite leaders say the need to cover at work spills over into their life outside of work, extending the pressure to keep parts of themselves hidden beyond the office. Many also see covering as a drag on their advancement, identifying it as a key factor that has slowed their career progression.

The Striking Paradox

Interestingly, the executives who report the highest levels of covering also report the most positive daily mood and the strongest loyalty to their organizations. Sixty-seven percent describe their mood as positive or very positive, and they post the highest employee Net Promoter Score (23) of any level, revealing a paradox. The leaders carrying the greatest concealment burden appear to also thrive under it.

C-suite leaders may experience more stress and identity covering due to their highly visible positions where perception could impact their credibility. Their paradoxical higher mood and loyalty might stem from having succeeded within the system, reinforcing an internal locus of control that frames challenges as conquerable rather than unfair. They may view the organization as a meritocratic path to success reflecting both leadership advantages and psychological justification for their personal compromises.

Why Uncover?

The implications of covering extend far beyond the C-suite. Across levels, employees report covering upward more than in any other direction. Sixty-six percent (66%) say they primarily hide aspects of themselves from senior leaders and direct supervisors. When executives model covering, others learn the environment is not fully safe. This contributes to a very real business challenge reported by nearly every CEO we have ever worked with: the “permafrost” — a frozen middle where information stops flowing, truth is softened and innovation is stifled.

Covering isn’t just a personal cost for leaders. It shapes culture, suppresses upward communication, and ultimately impacts organizational performance. The covering paradox at the top is no longer a sustainable model for the workplace. Recognizing this permafrost exists is how organizations can regain the agility the future demands.

What Can Leaders Do?

C‑suite leaders are uniquely positioned to turn covering from an invisible tax on performance into a visible test of leadership courage. The choice is no longer whether people are covering (most of are) but whether those at the top are willing to redesign the conditions that make hiding feel safer than being real. That requires treating covering not as an HR side issue, but as a core business risk that quietly erodes creativity, quality of decision making, and discretionary effort at scale.

- Talk about it. In our study, mere exposure to the concept of covering through a 10-minute survey shifted behavior: 39% of participants reported greater awareness of their own covering, 33% reported increased empathy toward others, and 21% said they felt motivated to help reduce the pressure on others to cover. Naming the phenomenon matters. It makes the invisible visible and actionable.

- Move first and model what “uncovered” looks like. Executives often ask for openness while keeping their own armor firmly in place. The most credible C-suite leaders go first. They share moments when they felt pressure to edit their identity, acknowledge past complicity in rewarding sameness, and describe how they are personally experimenting with showing more of who they are. When a CEO admits to once hiding a health issue, caregiving responsibility, or aspect of identity to appear more “leader-like,” and explains what they will do differently now, it recalibrates what honesty looks like across the organization. Modeling also shows up in routines, not just language: leaving early for family obligations, blocking time for therapy or faith observance, or naming neurodiversity or disability without euphemism—and ensuring those disclosures carry no downside in evaluations, stretch assignments, or succession plans for employees. These everyday signals do more cultural work than a dozen memos or company town halls.

- Invest in your people. Employees who report a willingness to change their own behavior so others feel less pressure to cover also report significantly more positive views of their organization. They score higher on employee Net Promoter Score and rate career mobility, development opportunities, promotion fairness, and respect more favorably. People who believe their organization invests in them are more likely to take prosocial risks that increase psychological safety for others.

- Identify change agents, such as having personal experience with covering. Leaders with firsthand experience of covering are often the most credible allies. Having navigated the pressure to edit themselves, they tend to recognize the quiet costs of conformity and are more willing to create space for others to show up without penalty. Their impact doesn’t come from calling behavior out, but from signaling safety and backing people when they take interpersonal risks, naming what others hesitate to say, and quietly removing friction that makes authenticity costly.

- Turn insight into structural commitments – Once leaders understand how covering is playing out in their company, they need to ask hard, structural questions: Where are we explicitly or implicitly rewarding conformity? Where do our promotion, performance, and succession criteria still assume a narrow template of what “leader material” looks or sounds like? From there, the C‑suite can commit to specific changes: rewriting leadership competency models to value perspective‑taking and psychological safety, revisiting dress and appearance expectations, rethinking “face time” norms, and pressure‑testing major talent decisions for subtle penalties against people who show up differently.

Uncovering doesn’t mean oversharing. It means modeling calibrated vulnerability—naming ambiguity when it matters, rewarding honesty in others, and removing structural penalties for being human.

Without removal of these rigid expectations, covering continues to be detrimental to the workplace by deteriorating employee engagement, creativity, innovation, performance, productivity and career progression. An environment where employees can choose to share versus choose to cover frees people to do their best work.

Written by Tia Katz.

Add CEOWORLD magazine as your preferred news source on Google News

Follow CEOWORLD magazine on: Google News, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.License and Republishing: The views in this article are the author’s own and do not represent CEOWORLD magazine. No part of this material may be copied, shared, or published without the magazine’s prior written permission. For media queries, please contact: info@ceoworld.biz. © CEOWORLD magazine LTD